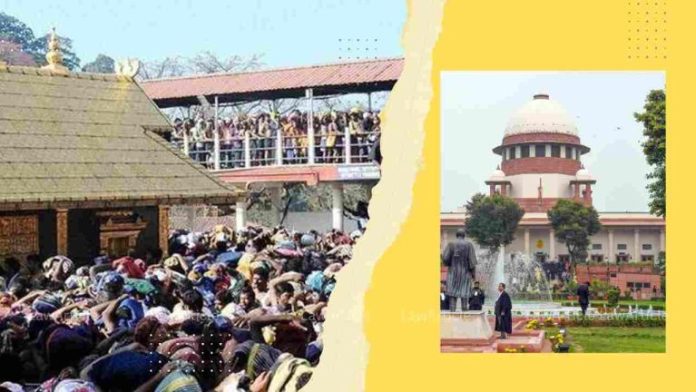

The Sabarimala Case- Religion and Freedom.

Background of Sabarimala Temple and Its Traditions

The case also brought to light broader social issues related to gender equality, women’s rights, and the role of religious customs in modern society. The widespread debate reflected deep-seated cultural and religious sentiments, with protests and demonstrations both in favor of and against the ban.

The Sabarimala Temple, situated in the Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala’s Western Ghats, is one of the most famous and sacred Hindu temples in India. It is dedicated to Lord Ayyappa, a deity revered as a celibate (Naishtika Brahmachari). The temple attracts millions of devotees annually, especially during the pilgrimage season, which involves a rigorous 41-day penance period where devotees abstain from worldly pleasures and adhere to strict rituals.

One of the distinctive and controversial aspects of the Sabarimala tradition is the prohibition on women of menstruating age (10-50 years) from entering the temple. This exclusion is based on the belief in Lord Ayyappa’s celibate status and the associated need to maintain the temple’s sanctity by keeping away those who might disrupt this celibacy through their mere presence.

Legal Precedent of The Sabarimala Case

In 1991, the Kerala High Court upheld the ban on women of menstruating age entering the Sabarimala Temple in the case of S. Mahendran v The Secretary, Travancore. The court ruled that the exclusion was constitutional and a reasonable practice, given its long-standing tradition and the belief in maintaining the sanctity of the temple. The court held that the practice did not violate the rights of women under the Indian Constitution, thus reinforcing the temple’s customary practices.

The Petition by the Indian Young Lawyers Association

In 2006, the Indian Young Lawyers Association filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court of India challenging the ban on women’s entry to the temple. The petitioners argued that the prohibition violated various fundamental rights of women guaranteed under the Indian Constitution, including:

- Article 14 (Right to Equality): The exclusion of women based on their biological characteristics is discriminatory.

- Article 15 (Prohibition of Discrimination): The practice discriminates against women based on their sex.

- Article 17 (Abolition of Untouchability): The exclusion is a form of untouchability based on notions of purity and impurity.

- Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty): The practice infringes upon the dignity and liberty of women.

- Article 25 (Freedom of Religion): The restriction impinges on women’s right to freely practice and profess their religion.

The Association contended that the ban on women’s entry was not an essential religious practice protected under Article 25 and that such practices should be subject to constitutional scrutiny.

Legal and Social Implications

The case brought to the forefront the conflict between traditional religious practices and contemporary constitutional values of equality and non-discrimination. It questioned whether religious practices could override fundamental rights and whether the state and judiciary could intervene in religious matters to uphold constitutional principles.

The case also sparked widespread debate and protests across India, with strong opinions on both sides. Supporters of the ban argued that the temple’s traditions and the deity’s celibate nature must be respected, while opponents viewed the practice as a regressive and patriarchal imposition that undermines women’s rights.

Supreme Court’s Involvement

The Supreme Court’s involvement in the case represented a critical examination of the balance between religious freedom and gender equality. The Court’s decision had the potential to set a significant precedent for similar cases involving religious practices and their compatibility with constitutional values.

The landmark judgment on 28 September 2018, which allowed women of all ages to enter the Sabarimala Temple, thus became a pivotal moment in India’s ongoing struggle to reconcile traditional beliefs with modern principles of equality and justice.

Issues Formulated by the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court considered several key issues in its deliberation:

- Right to Equality and Non-Discrimination: Whether the restriction on menstruating women violates the fundamental rights to equality and non-discrimination under Articles 14 and 15.

- Religious Denomination: Whether the devotees of Lord Ayyappa constitute a separate religious denomination with the autonomy to regulate their own religious practices under Article 26.

- Essential Religious Practice: Whether the exclusion of women is an essential religious practice protected under Article 25.

- Public Worship Rules: Whether Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Rules, which permits religious denominations to exclude women, is constitutional.

- Contradiction with Parent Legislation: Whether the Public Worship Rules enabling the exclusion to contradict the parent legislation that prohibits discriminatory practices.

Summary of Arguments

Petitioners’ Arguments

- Violation of Right to Equality (Article 14): Exclusion of women based on menstruation is discriminatory and violates the right to equality.

- Violation of Prohibition of Discrimination (Article 15): Banning women from entering solely on the basis of sex is explicitly prohibited.

- Violation of Abolition of Untouchability (Article 17): Exclusion based on menstruation is a form of social ostracism akin to untouchability.

- Violation of Right to Life and Personal Liberty (Article 21): The practice infringes on women’s dignity and personal liberty.

- Violation of Freedom of Religion (Article 25): The exclusion impinges on women’s right to freely practice their religion and is not an essential religious practice.

- Inconsistency with Public Worship Rules: Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules contradicts the parent legislation that prohibits discriminatory practices.

- Non-Essential Religious Practice: The exclusion is a social custom, not an integral part of the religion, and should not be protected.

- Constitutional Morality: The judiciary must uphold constitutional morality and protect fundamental rights over discriminatory customs.

Respondent’s Arguments (Temple Authorities and Supporters)

- Preservation of Religious Tradition: Exclusion of women is a long-standing tradition essential to preserving the temple’s sanctity.

- Distinct Religious Denomination (Article 26): Devotees of Lord Ayyappa form a distinct denomination with the right to manage their own religious practices.

- Essential Religious Practice: The exclusion is an essential religious practice integral to the worship of Lord Ayyappa, protected under Article 25.

- Validity of Rule 3(b): Rule 3(b), allowing exclusion based on custom, is consistent with maintaining temple traditions.

- Non-Violation of Fundamental Rights: The practice is a necessary aspect of religious traditions and does not violate women’s fundamental rights.

- Judicial Non-Interference: Courts should not interfere in religious practices unless they are harmful or oppressive.

- Support from Religious Community: The practice is supported by the majority of devotees and holds societal and cultural significance.

Judgment

The Supreme Court, by a 4:1 majority, ruled that the exclusion of women violated fundamental rights. The key points from the judgment include:

- Right to Equality: The exclusion of women was deemed discriminatory under Article 15 and not an essential religious practice under Article 25.

- Religious Denomination: The Court ruled that devotees of Lord Ayyappa do not constitute a separate religious denomination.

- Essential Religious Practice: The majority opinion held that the practice of excluding women was not essential to the religion.

- Public Worship Rules: Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules, which permitted the exclusion of women, was declared unconstitutional.

The majority opinion, delivered by Chief Justice Dipak Misra (for himself and Justice A.M. Khanwilkar) and supported by Justices Nariman and Chandrachud, emphasized that the practice infringed upon the fundamental rights to equality, liberty, and religious freedom. Justice Chandrachud added that social exclusion based on ideas of purity was akin to untouchability and violated Article 17.

Justice Indu Malhotra, in her dissenting opinion, argued that matters of religious practices should not be interfered with by the courts unless they cause harm or are oppressive, such as the practice of Sati.

- The judgment reaffirmed the supremacy of constitutional rights over religious practices that discriminate based on gender.

- The decision has significant implications for similar practices in other religious contexts, emphasizing the need for inclusivity and equality.

- Justice Malhotra’s dissent highlights the ongoing debate over the role of the judiciary in matters of religion and tradition.

Backlash

The judgment precipitated significant backlash from conservative quarters, including protests, rallies, and legal challenges. Critics argued that the Court’s decision interfered with religious traditions and beliefs, portraying it as an imposition of Western values on Indian customs. The protests often turned violent, with clashes between protesters and police reported near the temple premises and in other parts of Kerala. Political parties also capitalized on the issue, with some supporting the protesters to gain electoral support from conservative voter bases. The backlash underscored the challenges of implementing progressive legal reforms in societies deeply rooted in tradition and religious practices, revealing enduring tensions between constitutional principles and cultural conservatism in India.

Court Outlook and Opinion

The Supreme Court’s judgment reflected a commitment to upholding constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination over traditional religious practices. It emphasized the importance of constitutional morality in interpreting and applying fundamental rights, asserting the judiciary’s role in safeguarding these rights even in matters of religious faith and practice. The decision challenged the notion that religious customs could justify discrimination or exclusion based on gender, setting a significant precedent for future cases involving conflicts between religious practices and constitutional guarantees.

Social Implications

The judgment had profound social implications, sparking intense debate and reactions across India. It empowered women’s rights activists and advocates for gender equality, who hailed it as a landmark victory for women’s rights and a step towards dismantling patriarchal norms in religious settings. However, the ruling also ignited strong opposition from traditionalists, religious groups, and devotees of Sabarimala, leading to widespread protests, demonstrations, and social unrest, particularly in Kerala. The controversy highlighted deep-seated cultural and religious sensitivities regarding menstrual taboos and purity, underscoring the complex intersection of gender, religion, and societal norms in Indian society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Sabarimala judgment by the Supreme Court of India marked a significant milestone in the country’s legal and social landscape. The Court’s decision to strike down the centuries-old practice of barring women of menstrual age from the Sabarimala Temple reaffirmed constitutional principles of equality, non-discrimination, and personal liberty. By emphasizing constitutional morality over religious customs that perpetuate gender inequality, the judgment set a precedent for future cases challenging discriminatory practices in the name of religion.

However, the ruling also triggered intense social and political reactions, exposing deep-seated societal divisions and resistance to change. The widespread protests and backlash from traditionalists highlighted the complex interplay between religious beliefs, cultural norms, and constitutional rights in India. Despite these challenges, the judgment propelled debates on gender equality and religious freedom to the forefront of public discourse, encouraging broader societal introspection and legal scrutiny of discriminatory practices across religious institutions.

Moving forward, the Sabarimala case serves as a reminder of the judiciary’s pivotal role in upholding fundamental rights and promoting inclusive practices within diverse religious contexts. It underscores the ongoing need for balanced deliberation between preserving cultural heritage and advancing principles of justice and equality in a pluralistic society like India’s.

Also Read:

Rights of undertrial prisoners in India

How To Send A Legal Notice In India