Introduction

The case of Lily Thomas v. Union of India revolves around the question of whether Members of Parliament or the Legislature should be disqualified after being convicted in a criminal case. Two petitions were filed before the Supreme Court, highlighting the increasing number of elected officials with criminal cases pending against them and the lack of legislative action to address this issue. The petitioners argued that the provision allowing a convicted legislator to continue serving until the disposal of their appeal is unconstitutional, as it contradicts the uniform disqualifications set forth in the Constitution. On the other hand, the state argued that such provisions are necessary due to the high frequency of acquittals in higher courts. The Court’s decision in this case has significant implications for the integrity of the electoral process and the accountability of elected representatives in India.

Background of the case

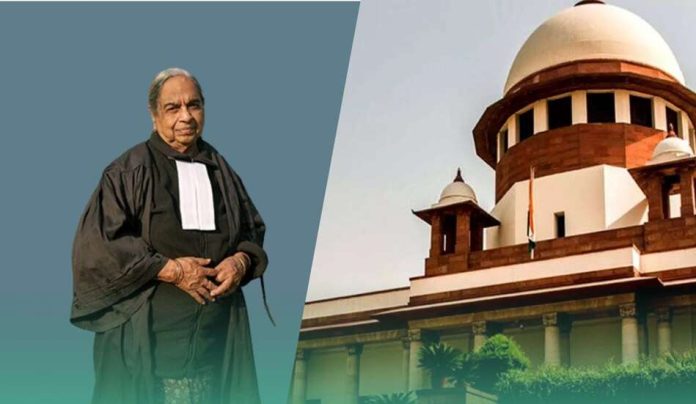

The case concerns the disqualification of Members of Parliament or the Legislature following criminal convictions, adjudicated by a two-judge bench comprising Justices A.K. Patnaik and S.J. Mukhopadhaya in 2013. Two petitions were brought before the Supreme Court, one by Advocate Lily Thomas and the other by Lok Prahari, represented by its General Secretary S.N. Shukla, both addressing the issue of whether MLAs or MPs should face disqualification upon criminal conviction.

The phenomenon of criminalization within politics strikes at the foundation of democratic governance, as it directly impacts the integrity of electoral processes. Statistics reveal a marked increase in the presence of individuals with criminal records within state and central legislatures since India’s independence.

According to the Association for Democratic Reforms, the percentage of MPs with pending criminal cases rose from 24% in 2004 to 43% in the 2019 Parliament. This trend underscores a concerning trajectory for the future of democratic governance in the country. The Parliament’s failure to enact legislation establishing guidelines for penalties related to legislators with criminal backgrounds or convictions is emblematic of entrenched interests within the legislative body. Presently, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 governs the disqualification of elected legislators.

Sections 8(1), 8(2), and 8(3) of the RP Act stipulate that a legislator convicted of specified offenses shall be disqualified from holding office. However, Section 8(4) of the Act provides a provision whereby disqualification, upon conviction, is deferred for a period of three months or until the disposal of any appeals or revision applications.

It is this provision, Section 8(4), which is the subject of challenge in the writ petitions under consideration. Hence, the Court was tasked with determining whether Section 8(4) is ultra vires to constitutional provisions. The Anti-defection law, initially enacted in 1985 and subsequently reinforced in 2002, is pertinent to this context. The 52nd Amendment to the Constitution introduced the 10th Schedule, outlining the procedure for the disqualification of legislators.

FACTS OF THE CASE

- Two writ petitions were filed before the Supreme Court by Advocate Lily Thomas and Lok Prahari, represented by its General Secretary S.N. Shukla. The petitions raised the question of whether Members of Legislative Assemblies (MLAs) or Members of Parliament (MPs) should face disqualification upon criminal conviction.

- The criminalization of politics has seen a significant rise in the number of elected officials with pending criminal cases.

- Statistics from the Association for Democratic Reforms indicated a steady increase in the percentage of MPs with pending criminal cases over the years.

- The Representation of the People Act, 1951 governs the disqualification of elected legislators. Sections 8(1), 8(2), and 8(3) of the RP Act provide for disqualification upon conviction for specified offenses.

- However, Section 8(4) of the Act allows for the deferment of disqualification, providing a three-month window or until the disposal of any appeals or revision applications. The petitioners challenged the constitutionality of Section 8(4) before the Supreme Court.

- The court was tasked with determining whether Section 8(4) violated constitutional provisions. The Anti-defection law, enacted in 1985 and reinforced in 2002, is relevant to this context, particularly the provisions outlined in the 10th Schedule of the Constitution regarding the disqualification of legislators.

ISSUES

- Did the Supreme Court consider whether Parliament had the legislative power to enact Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951?

- How did the Court interpret Articles 102(1)(e) and 191(1)(e) of the Constitution in relation to Parliament’s authority to make laws providing disqualifications for membership of Parliament or State Legislatures?

- Was the validity of Section 8(4) of the RP Act, 1951 assessed in light of its consistency with constitutional provisions?

- Did the Court examine whether there was consistency in the criteria for disqualification for both elections and continued membership in Parliament or State Legislatures?

- Were the constitutional provisions regarding the automatic vacancy of a seat upon the disqualification of a Member of Parliament or State Legislature analyzed by the Court?

- What was the impact of the Court’s judgment on existing cases involving sitting Members of Parliament or State Legislatures affected by Section 8(4)?

ARGUMENT

Petitioners’ Arguments

- Senior Advocate Fali S. Nariman, representing the petitioners, argued that the opening words of clause (1) of Articles 191 and 102 of the Indian Constitution clearly indicate that the same disqualifications apply to individuals being chosen as members of either House of Parliament or the State Assembly/Legislative Council.

- They emphasized that there should be uniformity in disqualifications for individuals seeking election and those already serving as members, as stated in the Constitution.

- Citing the Supreme Court’s constitutional bench judgment in Election Commission of India v. Saka Venkat Rao, they highlighted that the court had previously ruled that disqualifications were the same for both standing in an election and continuing as a member.

- The petitioners urged the court to strike down Section 8(4) as ultra vires, arguing that Parliament lacks the legislative power to enact such a provision.

State’s Arguments

- Represented by Assistant Solicitor General (ASG) Mr. Siddharth Luthra, the state contended that the validity of Section 8(4) had already been upheld by the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court in K. Prabhakaran v. P. Jayarajan.

- The ASG argued that the high frequency of acquittals in higher courts justifies the necessity for Section 8(4), which allows for the delay in the disqualification of sitting members of Parliament or State Legislatures pending appeals or revisions.

- By providing for such a provision, Parliament aimed to address the issue of potential wrongful disqualifications due to frequent acquittals in appellate courts.

OBSERVATION OF THE COURT

- The Constitution intended to establish uniform disqualifications for individuals seeking election and those already serving as members of either House of Parliament or the State Assembly/Legislative Council.

- Articles 102(1)(e) and 191(1)(e) of the Constitution confer power on Parliament to enact laws regarding disqualifications for both prospective and sitting members.

- Articles 101(3)(a) and 190(3)(a) expressly prohibit Parliament from deferring the date on which disqualifications come into effect for sitting members.

FINDING OF THE COURT

- The effect of disqualification under Articles 102(1) and 190(1) of the Constitution results in the automatic vacation of the member’s seat.

- Parliament cannot enact a provision, such as Section 8(4) of the Act, to defer the date of disqualification for sitting members.

- Parliament exceeded its powers conferred by the Constitution by enacting Section 8(4) of the Act.

JUDGEMENT

- The Court holds that Parliament has the power to enact laws establishing uniform disqualifications for both prospective and sitting members.

- Section 8(4) of the Act is declared ultra vires the Constitution as it goes against the express limitations set forth in Articles 101(3)(a) and 190(3)(a).

- The declaration made by the Court in this judgment will not affect sitting members who were previously protected by Section 8(4) until the date of pronouncement of this judgment.

- However, if any sitting member is convicted of offenses mentioned in Section 8(1), (2), or (3) after this judgment, their membership will not be saved by Section 8(4), irrespective of any pending appeals or revisions against the conviction or sentence.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Supreme Court declared Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 ultra vires the Constitution. The Court emphasized that Parliament lacks the power to enact provisions that defer the date of disqualification for sitting members, as it contradicts the uniform disqualifications mandated by the Constitution. This decision marks a crucial step towards ensuring the integrity of the electoral process and holding elected representatives accountable for their actions. Additionally, the Court’s ruling provides clarity on the constitutional limitations of Parliament’s legislative powers regarding the disqualification of legislators convicted in criminal cases

Also Read:

Rights of undertrial prisoners in India

How To Send A Legal Notice In India